I like to imagine how different the posts on LinkedIn might have looked when I first entered FTSE commercial life in the 90s.

Have a quick scroll… the brilliant posts around Mental Health First Aid, the importance of psychological safety and emotional intelligence and photographs of employees having fun together doing things only vaguely related to work would have been viewed as ‘nice to have’ or downright fluffy…

But as always, if we look to hard science we can find sound reasons why this evolution and investment in our people has gained huge traction. Mental health disorders cause more absence and reduced productivity at work than bad backs, broken limbs and every other muscular-skeletal issue added together.

A psychology study just published (March 2023) helps us understand more about the specific things that make a workplace or occupation ‘high risk’ for mental health problems – taking aside the actual nature of the work itself or the socio-economic profile of people recruited to that job.

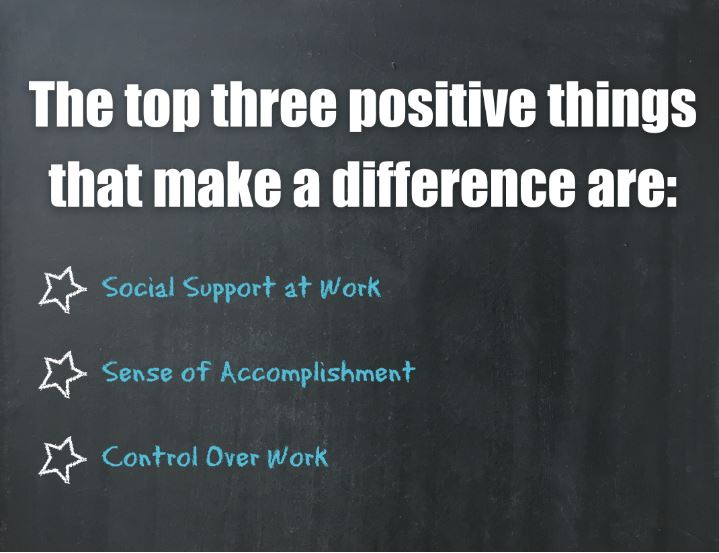

People who reported that they had these three things in their work-life were significantly less likely to experience mental health issues at work. Unsurprisingly the ‘negative top three’ look quite similar:

1) Excessive Job Demands

2) Low Social Support at Work

3) Lack of Control over work

The research also found that staying in jobs where excessive demands, low support and lack of control persist over time increases the risk of mental health issues – we don’t become ‘immune’ or get used to it.

This is one of the first studies to be ‘adjusted’. Removing the jargon means that the results took into account the characteristics of the occupation (for example how dangerous or ‘stressful’ it was), the social and economic patterns of people who are recruited into particular roles (the old terminology of ‘blue collar/white collar’) and the prior mental health of the people studied or any life events that may have impacted their mental health.

What this ‘adjustment’ means in practical terms for those of us who just want to get on and do something about workplace absence or increasing productivity and engagement at work, is that there are no excuses! The top three are the top three.

Research like this is useful because it can remove any smoke and mirrors or doubt about what we should actually prioritise and get on and do.

So provide opportunities for social support, ask people whether they feel a sense of accomplishment – and if not what would and give people as much control and autonomy as you can and you won’t go far wrong!

Equally, continue with excessive work demands and social events or environments that don’t take account of your diverse workplace and expect nothing more or less than higher absence and lower productivity than your competitors.

Sometimes science does make it that simple!